Kleptocracy undermines democracy. Bolstering the capacity of journalists and civil society to respond to it at its source must be a central priority of the international community.

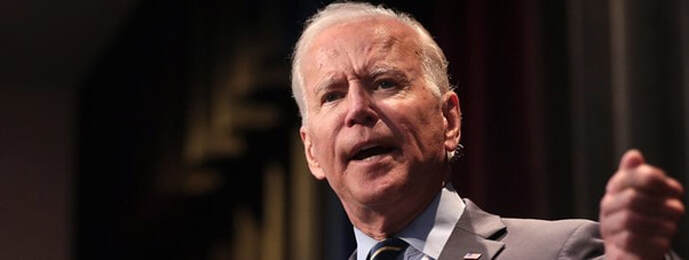

President Joe Biden brought with him to the White House the hope that a US President would finally lead a global effort to fight back against kleptocracy, corruption and illicit finance. The omens were positive. Writing in 2018, the future president laid out how Washington and Western allies should respond to the threat posed by illicit finance, urging action from all those responsible for its facilitation. In 2020, Biden emphasised this message, committing to combat corruption ‘as a core national security interest and democratic responsibility’ and ‘lead efforts internationally to bring transparency to the global financial system, go after illicit tax havens, seize stolen assets, and make it more difficult for leaders who steal from their people to hide behind anonymous front companies’.

Pronouncements once he took office continued to raise hopes. In June 2021, the White House published its Memorandum on Establishing the Fight Against Corruption as a Core United States National Security Interest, focused on enhancing every element of the US response to kleptocracy and illicit finance. In December 2021, Biden further underscored his credentials with the publication by the White House of the US Strategy on Countering Corruption, a widely feted document; and sought to bolster efforts to address the illicit finance threats to democratic values via his much-anticipated Summit for Democracy. The summit’s focus on defending against authoritarianism, advancing respect for human rights and addressing and fighting corruption aims to trigger a ‘year of action’ by global leaders and civil society alike, to undertake meaningful reforms and initiatives to tackle these contemporary threats faced by democracies.

Starting at Home

Triggered by the passing of the US Anti-Money Laundering Act 2020, much of the past 12 months in the US has focused on ‘fixing the home base’, in an attempt to begin to address the systemic national failings that are exploited by the corrupt and kleptocrats as they seek to place the proceeds of their crime beyond the reach of law enforcement agencies. Greater corporate transparency is promised along with a fundamental modernisation of US anti-money laundering laws.

The US is not alone in needing to address domestic shortcomings that have international consequences. The UK, another facilitator of global illicit financial flows, faces similar failings – such as the overdue reform of Companies House and the introduction of a register of overseas property ownership – that need to be addressed with the same energy the US is applying.

But alongside the need for action from the global facilitators of illicit finance, the countries that suffer at the hands of kleptocrats and the corrupt must also take action to strengthen their national financial integrity. In countries where the state or key members of the political elite are complicit in this activity, it falls to civil society and investigative journalists to bring to light national failings and highlight and press for the reforms that are needed. Empowering these non-governmental actors to highlight corrupt activity and press for transparency and accountability is a critical element of the global effort to reverse the impunity felt by those that profit from corruption and kleptocracy. While more action is certainly needed by policymakers in London and Washington, restricting kleptocracy in the ‘first mile’, at its source, must also be prioritised.

Kleptocracy in the First Mile

Billions of dollars are stolen from lower capacity countries every year, money these countries can ill-afford to lose. But the impact of this loss of funds does not impact all citizens equally. While the poorest who rely on the state for support to survive and for the provision of vital services are significantly disadvantaged, the rich and powerful often benefit from this corrupt activity either directly as the malign actors, or indirectly by receiving bribes or favours for facilitating this kleptocratic activity.

Often, those who are accountable for identifying, investigating and prosecuting this activity are precisely those that benefit from, or are closely connected to, this theft of national wealth. The state-based systems for monitoring and holding to account those committing these crimes are thus neutered.

It is therefore imperative that others – those from civil society and the investigative journalism community – that care deeply about the open and fair functioning of a state are empowered to fill the gap left by this dereliction of duty by many in the state apparatus.

Yet to do this effectively, these concerned citizens need the knowledge that enables them to hold the corrupt to account. They need to understand the laws and regulations that should be applied to restrict and prosecute corrupt activity; they need to understand the policy accountability chain – from the responsible local government bodies up through international standard setters; they need to be aware of the internationally-agreed standards that a country should be applying to tackle financial crime; they should be aware of the responsibilities that are placed on private sector actors whose skills and services are used by the corrupt to move money out of their home countries and into the international system where it can easily hide; and should be aware of the networks and tools that could support their work.

Another challenging factor is that international standard setters can often be disconnected from local perspectives. This is because the Financial Action Task force (FATF), the global financial crime watchdog, and its network of regional affiliates, may find their engagement with local actors limited to those that are introduced by the host country itself in its evaluations. This means that in kleptocratic countries, access to grassroot communities and journalists that will hold government to account is restricted, if provided at all. While the FATF has developed the beginnings of a mechanism by which grassroot insights can be channelled into the FATF and its regional bodies, this remains nascent. Other international watchdogs, such as the World Bank and the IMF, most often follow the FATF’s lead when it comes to anti-money laundering – again, missing opportunities for an on-the-ground reality check.

Thus, corrupt individuals and kleptocratic politicians and their families continue to loot their countries’ wealth with impunity in many countries around the world. Once this money is across the border, out of the local region and into the international financial system, the chances of identifying, seizing and returning the funds are vanishingly small. Thus strengthening the first mile and the financial hubs that facilitate this movement beyond the reach of law enforcement is critical to fight this corrupt activity. The organs of state charged with identifying and investigating this activity are often muzzled, underfunded and simply unable to conduct their oversight and judicial responsibilities, a vacuum that civil society and the media are left to fill.

From Panama City to Nairobi, and Beyond

These are not theoretical challenges. Kleptocrats across the world are constantly at work, moving their funds out of source countries into the international financial system where they are often hidden forever.

For example, the most recent international release of leaked documents, the Pandora Papers, show how politicians and individuals in power arrange offshore interests to avoid taxes and facilitate corrupt activities.

Take the Kenyatta family in Kenya. President Uhuru Kenyatta made himself a spokesman against corruption, arguing on behalf of the country’s poor and against government officials looting public resources. Yet the Pandora Papers show that he and seven members of his family are connected to 11 offshore companies and foundations. Meanwhile, in 2016, Muhoho Kenyatta, the president’s brother, who manages large sections of the family businesses, owned an offshore company with a portfolio of cash, stocks and bonds worth $31.6 million. Then there is the Varies Foundation, which was registered with Panama’s company registry in 2013 for the benefit of the president’s mother, Ngina Kenyatta. In this case there in no mention of the family in any of the paperwork, instead all the foundation’s officers are employed by an offshore law firm in Panama called Alemán, Cordero, Galindo & Lee. At the very least, these activities are unbecoming of the family of a political dynasty; at worse they suggest a desire to create financial arrangements that are beyond the scrutiny of the authorities in their home country.

An empowered civil society and media community can help bring these stories to light, making kleptocratic leaders accountable for their actions. These issues transcend national borders, with the benefits of corrupt activity travelling across the world, making it ever more challenging for local journalists to effectively follow the money and carry out financial crime investigations. This is why supporting the building of connections and networks among investigative journalists and civil society actors and linking their findings to international bodies is essential.

Another investigation, Chavismo Inc, is an example of a transnational project following both money and actors connected to Venezuelan kleptocrats. By working together with journalists from across Latin America, the team hopes to gain insight into these illicit activities and amplify their stories by connecting with the global media community. The open database currently tracks over 5,000 people and entities directly or indirectly involved with Venezuelan funds. More specifically, 751 persons of interest are listed due to their connections with Chavismo government businesses such as high-level contractors with access to power, former senior officials and intermediaries with contacts in the administration.

Venezuelan funds pass mainly through the Panamanian financial system, with Venezuelan clients contributing more than $2.8 million in the country up to 2019. The project identified 242 limited companies in Panama with over 380 links to persons of interest in Venezuela. Out of these companies, eight are listed by the US Office of Foreign Assets Control and several others are currently undergoing judicial investigations around the world on allegations of money laundering and bribery. The existence of this database allows other journalists, activists and members of the global anti-financial crime community to know what to look for, making it easier to follow the money by looking at these individuals or companies as a starting point. Projects like this and the further investigations they can trigger can allow for a stronger response in the first mile, pressing for positive systemic change in national efforts to combat illicit financial flows.

Turning the Tide

As these cases illustrate, if funds are stolen by those in positions of power and with access to the international financial system, they can quickly move their ill-gotten gains beyond the reach of law enforcement investigations and are almost certainly lost forever. It is with this concern in mind that the international community must work harder to strength the response to kleptocracy and illicit finance in the first mile.

First, countries such as the US and the UK must prioritise overdue reforms to their own systems that are exploited by those seeking to abuse these weaknesses to place their illicit financial gains beyond the reach of law enforcement.

Second, democracies such as the US and the UK must work harder to strengthen, support and protect those investigative journalists and members of civil society conducting the dangerous work to uncover corrupt and kleptocratic activity in source countries. They must empower these activists to contribute to societal pressure on government institutions and regulated businesses to comply with their international obligations to fight illicit finance. Increasing their knowledge of global standards and norms on anti-money laundering and other forms of illicit finance, to which countries should adhere, as well as facilitating an understanding of how these standards should be implemented in practice, will provide them with greater capacity to achieve these objectives. The international community should also support these activists to bring their stories to a relevant international audience, thereby widely disseminating the shortcomings and wrong-doings they have identified in the hope that international scrutiny will drive domestic change.

Third, these leading countries must use diplomatic and trade pressures to encourage reforms that strengthen the integrity of the financial system. While not perfect, the global standards of the FATF provide a strong basis from which to press countries to act.

Finally, the international community must not turn a blind eye to illicit finance. Failing to defend international standards robustly and treating them as ‘nice to have’ in international dialogues contributes to the erosion of democratic values.

Securing Democracy

The activities of the corrupt and kleptocrats rely on a series of steps: from abusing their status and access to profit from their positions of power and influence; to the failings of the global financial centres that allow these actors to move their ill-gotten gains beyond the reach of law enforcement and thus to enjoy the fruits of their crime. These are not just crimes, they are actions that threaten democracy as they display contempt for the trust that voters have placed in them and undermine faith in institutions, hollowing out their ability to deliver the vital services required in countries that can least afford to lose invaluable financial resources.

Empowering civil society and investigative journalists to hold politicians and officials to account, supporting and promoting their work, and ensuring the international community responds to the criminality they identify must be a fundamental commitment of all those that believe in democracy and will be a key contributor to ensuring democracies remain responsive and resilient.

The views expressed in this article are the authors’, and do not represent those of RUSI or any other institution.

This article has been produced as part of a project funded by the National Endowment for Democracy.

President Joe Biden brought with him to the White House the hope that a US President would finally lead a global effort to fight back against kleptocracy, corruption and illicit finance. The omens were positive. Writing in 2018, the future president laid out how Washington and Western allies should respond to the threat posed by illicit finance, urging action from all those responsible for its facilitation. In 2020, Biden emphasised this message, committing to combat corruption ‘as a core national security interest and democratic responsibility’ and ‘lead efforts internationally to bring transparency to the global financial system, go after illicit tax havens, seize stolen assets, and make it more difficult for leaders who steal from their people to hide behind anonymous front companies’.

Pronouncements once he took office continued to raise hopes. In June 2021, the White House published its Memorandum on Establishing the Fight Against Corruption as a Core United States National Security Interest, focused on enhancing every element of the US response to kleptocracy and illicit finance. In December 2021, Biden further underscored his credentials with the publication by the White House of the US Strategy on Countering Corruption, a widely feted document; and sought to bolster efforts to address the illicit finance threats to democratic values via his much-anticipated Summit for Democracy. The summit’s focus on defending against authoritarianism, advancing respect for human rights and addressing and fighting corruption aims to trigger a ‘year of action’ by global leaders and civil society alike, to undertake meaningful reforms and initiatives to tackle these contemporary threats faced by democracies.

Starting at Home

Triggered by the passing of the US Anti-Money Laundering Act 2020, much of the past 12 months in the US has focused on ‘fixing the home base’, in an attempt to begin to address the systemic national failings that are exploited by the corrupt and kleptocrats as they seek to place the proceeds of their crime beyond the reach of law enforcement agencies. Greater corporate transparency is promised along with a fundamental modernisation of US anti-money laundering laws.

The US is not alone in needing to address domestic shortcomings that have international consequences. The UK, another facilitator of global illicit financial flows, faces similar failings – such as the overdue reform of Companies House and the introduction of a register of overseas property ownership – that need to be addressed with the same energy the US is applying.

But alongside the need for action from the global facilitators of illicit finance, the countries that suffer at the hands of kleptocrats and the corrupt must also take action to strengthen their national financial integrity. In countries where the state or key members of the political elite are complicit in this activity, it falls to civil society and investigative journalists to bring to light national failings and highlight and press for the reforms that are needed. Empowering these non-governmental actors to highlight corrupt activity and press for transparency and accountability is a critical element of the global effort to reverse the impunity felt by those that profit from corruption and kleptocracy. While more action is certainly needed by policymakers in London and Washington, restricting kleptocracy in the ‘first mile’, at its source, must also be prioritised.

Kleptocracy in the First Mile

Billions of dollars are stolen from lower capacity countries every year, money these countries can ill-afford to lose. But the impact of this loss of funds does not impact all citizens equally. While the poorest who rely on the state for support to survive and for the provision of vital services are significantly disadvantaged, the rich and powerful often benefit from this corrupt activity either directly as the malign actors, or indirectly by receiving bribes or favours for facilitating this kleptocratic activity.

Often, those who are accountable for identifying, investigating and prosecuting this activity are precisely those that benefit from, or are closely connected to, this theft of national wealth. The state-based systems for monitoring and holding to account those committing these crimes are thus neutered.

It is therefore imperative that others – those from civil society and the investigative journalism community – that care deeply about the open and fair functioning of a state are empowered to fill the gap left by this dereliction of duty by many in the state apparatus.

Yet to do this effectively, these concerned citizens need the knowledge that enables them to hold the corrupt to account. They need to understand the laws and regulations that should be applied to restrict and prosecute corrupt activity; they need to understand the policy accountability chain – from the responsible local government bodies up through international standard setters; they need to be aware of the internationally-agreed standards that a country should be applying to tackle financial crime; they should be aware of the responsibilities that are placed on private sector actors whose skills and services are used by the corrupt to move money out of their home countries and into the international system where it can easily hide; and should be aware of the networks and tools that could support their work.

Another challenging factor is that international standard setters can often be disconnected from local perspectives. This is because the Financial Action Task force (FATF), the global financial crime watchdog, and its network of regional affiliates, may find their engagement with local actors limited to those that are introduced by the host country itself in its evaluations. This means that in kleptocratic countries, access to grassroot communities and journalists that will hold government to account is restricted, if provided at all. While the FATF has developed the beginnings of a mechanism by which grassroot insights can be channelled into the FATF and its regional bodies, this remains nascent. Other international watchdogs, such as the World Bank and the IMF, most often follow the FATF’s lead when it comes to anti-money laundering – again, missing opportunities for an on-the-ground reality check.

Thus, corrupt individuals and kleptocratic politicians and their families continue to loot their countries’ wealth with impunity in many countries around the world. Once this money is across the border, out of the local region and into the international financial system, the chances of identifying, seizing and returning the funds are vanishingly small. Thus strengthening the first mile and the financial hubs that facilitate this movement beyond the reach of law enforcement is critical to fight this corrupt activity. The organs of state charged with identifying and investigating this activity are often muzzled, underfunded and simply unable to conduct their oversight and judicial responsibilities, a vacuum that civil society and the media are left to fill.

From Panama City to Nairobi, and Beyond

These are not theoretical challenges. Kleptocrats across the world are constantly at work, moving their funds out of source countries into the international financial system where they are often hidden forever.

For example, the most recent international release of leaked documents, the Pandora Papers, show how politicians and individuals in power arrange offshore interests to avoid taxes and facilitate corrupt activities.

Take the Kenyatta family in Kenya. President Uhuru Kenyatta made himself a spokesman against corruption, arguing on behalf of the country’s poor and against government officials looting public resources. Yet the Pandora Papers show that he and seven members of his family are connected to 11 offshore companies and foundations. Meanwhile, in 2016, Muhoho Kenyatta, the president’s brother, who manages large sections of the family businesses, owned an offshore company with a portfolio of cash, stocks and bonds worth $31.6 million. Then there is the Varies Foundation, which was registered with Panama’s company registry in 2013 for the benefit of the president’s mother, Ngina Kenyatta. In this case there in no mention of the family in any of the paperwork, instead all the foundation’s officers are employed by an offshore law firm in Panama called Alemán, Cordero, Galindo & Lee. At the very least, these activities are unbecoming of the family of a political dynasty; at worse they suggest a desire to create financial arrangements that are beyond the scrutiny of the authorities in their home country.

An empowered civil society and media community can help bring these stories to light, making kleptocratic leaders accountable for their actions. These issues transcend national borders, with the benefits of corrupt activity travelling across the world, making it ever more challenging for local journalists to effectively follow the money and carry out financial crime investigations. This is why supporting the building of connections and networks among investigative journalists and civil society actors and linking their findings to international bodies is essential.

Another investigation, Chavismo Inc, is an example of a transnational project following both money and actors connected to Venezuelan kleptocrats. By working together with journalists from across Latin America, the team hopes to gain insight into these illicit activities and amplify their stories by connecting with the global media community. The open database currently tracks over 5,000 people and entities directly or indirectly involved with Venezuelan funds. More specifically, 751 persons of interest are listed due to their connections with Chavismo government businesses such as high-level contractors with access to power, former senior officials and intermediaries with contacts in the administration.

Venezuelan funds pass mainly through the Panamanian financial system, with Venezuelan clients contributing more than $2.8 million in the country up to 2019. The project identified 242 limited companies in Panama with over 380 links to persons of interest in Venezuela. Out of these companies, eight are listed by the US Office of Foreign Assets Control and several others are currently undergoing judicial investigations around the world on allegations of money laundering and bribery. The existence of this database allows other journalists, activists and members of the global anti-financial crime community to know what to look for, making it easier to follow the money by looking at these individuals or companies as a starting point. Projects like this and the further investigations they can trigger can allow for a stronger response in the first mile, pressing for positive systemic change in national efforts to combat illicit financial flows.

Turning the Tide

As these cases illustrate, if funds are stolen by those in positions of power and with access to the international financial system, they can quickly move their ill-gotten gains beyond the reach of law enforcement investigations and are almost certainly lost forever. It is with this concern in mind that the international community must work harder to strength the response to kleptocracy and illicit finance in the first mile.

First, countries such as the US and the UK must prioritise overdue reforms to their own systems that are exploited by those seeking to abuse these weaknesses to place their illicit financial gains beyond the reach of law enforcement.

Second, democracies such as the US and the UK must work harder to strengthen, support and protect those investigative journalists and members of civil society conducting the dangerous work to uncover corrupt and kleptocratic activity in source countries. They must empower these activists to contribute to societal pressure on government institutions and regulated businesses to comply with their international obligations to fight illicit finance. Increasing their knowledge of global standards and norms on anti-money laundering and other forms of illicit finance, to which countries should adhere, as well as facilitating an understanding of how these standards should be implemented in practice, will provide them with greater capacity to achieve these objectives. The international community should also support these activists to bring their stories to a relevant international audience, thereby widely disseminating the shortcomings and wrong-doings they have identified in the hope that international scrutiny will drive domestic change.

Third, these leading countries must use diplomatic and trade pressures to encourage reforms that strengthen the integrity of the financial system. While not perfect, the global standards of the FATF provide a strong basis from which to press countries to act.

Finally, the international community must not turn a blind eye to illicit finance. Failing to defend international standards robustly and treating them as ‘nice to have’ in international dialogues contributes to the erosion of democratic values.

Securing Democracy

The activities of the corrupt and kleptocrats rely on a series of steps: from abusing their status and access to profit from their positions of power and influence; to the failings of the global financial centres that allow these actors to move their ill-gotten gains beyond the reach of law enforcement and thus to enjoy the fruits of their crime. These are not just crimes, they are actions that threaten democracy as they display contempt for the trust that voters have placed in them and undermine faith in institutions, hollowing out their ability to deliver the vital services required in countries that can least afford to lose invaluable financial resources.

Empowering civil society and investigative journalists to hold politicians and officials to account, supporting and promoting their work, and ensuring the international community responds to the criminality they identify must be a fundamental commitment of all those that believe in democracy and will be a key contributor to ensuring democracies remain responsive and resilient.

The views expressed in this article are the authors’, and do not represent those of RUSI or any other institution.

This article has been produced as part of a project funded by the National Endowment for Democracy.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed